By Allie Brawley | Photos by Abby Moran

This article was originally published in Cloverland Connections, September/October 2025.

When Dean Oswald was 6 years old, he and his family would vacation near Newberry, Michigan, where one of the highlights was watching wild bears forage at the local landfill. When Dean spotted a cub at the side of the road, he pleaded with his dad to pet the little creature. His dad cautioned that the protective mother bear would be nearby—and she soon appeared and nudged the cub back into the woods. Then she turned to the vehicle where Dean and his family watched and stood on her hind legs, a sign of threatening protection, and disappeared back into the woods with her cub.

“I was fascinated by that cub,” Dean recalled. “And I thought, someday I’ll have a bear cub.”

That childhood dream stayed with Dean throughout his life. Even as he served in the Marines, worked as a police officer and firefighter in Bay City, and raised four children with his wife Jewel, the dream of having a bear never left him. After retiring, Dean and Jewel bought an 80-acre property near Newberry in 1983 and moved north to begin building Dean’s childhood dream.

Shortly afterward, someone contacted Dean with a bear cub that needed a home—and his dream finally came true.

Dean remodeled their cabin, cleared the overgrown wood, and built the first bear enclosure by the lake. As he bonded with his first bear and then raised a second cub, word spread. Curious visitors started showing up to see the bears, photograph them, and sometimes even feed them. Recognizing the growing interest, Dean and Jewel began collecting food donations from local restaurants and grocery stores. That support continues to this day—five-gallon buckets filled with produce, freezer-burned meat, and sweets arrive regularly.

“We buy granola by the ton—20 tons at a time,” Dean laughs.

With growing public interest and appetites, Oswald’s Bear Ranch quickly became known for more than just bear sightings. When the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) closed landfills to spectators, a popular, low-cost way to view wildlife disappeared. As a result, the ranch emerged as a prime and meaningful opportunity to observe bears up close in a natural setting.

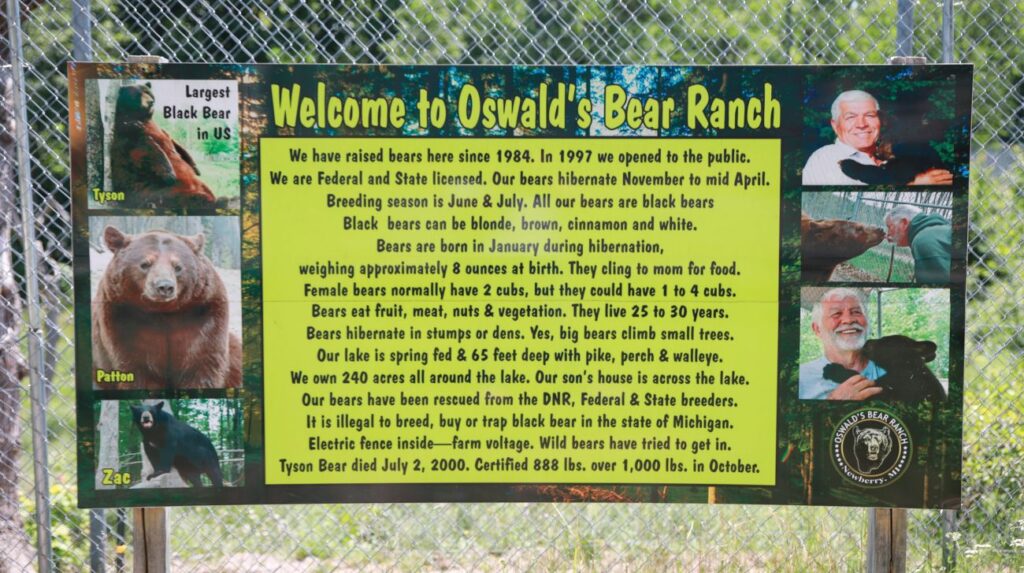

What began with just five bears has since grown to a thriving community of 50, divided among three expansive habitats for yearlings, males, and females. One enclosure spans an entire mile. Today, the ranch covers 250 acres and features pools for the young bears to cool off, elevated viewing platforms for visitors, and hibernation dens—some hand-built by Dean and others instinctively dug by the bears themselves.

To meet federal and state regulations, the Oswalds were required to build a 10-foot-high wire mesh fence with a four-foot-high perimeter fence. The cost strained the ranch’s operating budget. To help subsidize increasing operational costs, the Oswalds opened a gift shop selling hats, t-shirts, and bear gifts.

Today, Dean is recognized across the state as a bear rescuer. The DNR regularly contacts him when orphaned cubs need a home. Of the 50 bears at Oswald’s Bear Ranch, 48 were bottle-fed by Dean himself.

“When we started, we thought five or six cars a day would help us pay the bills,” he said. “Now we’ve had visitors from Australia, New Zealand, Germany, France, South Africa, and Newfoundland—all in one day.”

What began as a dream is now a beloved destination, operated with the help of Dean and Jewel’s family. Their son Monty helps during the season, and Monty’s son runs the gift shop and manages finances. Neighbors help cut apples and direct traffic. A local artist designed the entrance sign and a fellow bear enthusiast created the information board of frequently asked questions. Local specialized contractors installed fences, water lines, and electrical systems to safely support the bears.

“The best part about the ranch is that you’re with family and friends all day,” Monty says.

The ranch runs on simple pricing—$30 per vehicle—and offers the unique chance to get a photo with a bear cub. Many visitors seek out Dean himself to thank him, snap a photo, or meet his chipmunk companion “Chippy,” who eats sunflower seeds right from Dean’s hand.

Dean often sits near the habitat, smiling as visitors walk up to say, “Thanks for sharing your bears,” and fellow Marines pass by exclaiming, “Semper Fi.”

When asked what he’s most proud of, Dean doesn’t hesitate: “Just the fact that I accomplished a passion.”