Perhaps the most concise explanation of geocaching can be found on a bumper sticker that reads:

A scavenger hunt using multimillion-dollar satellites to find Tupperware in the woods.

If that’s not quite enough to get you interested in the sport—and yes, enthusiasts insist it’s a sport—then maybe a few more details might help.

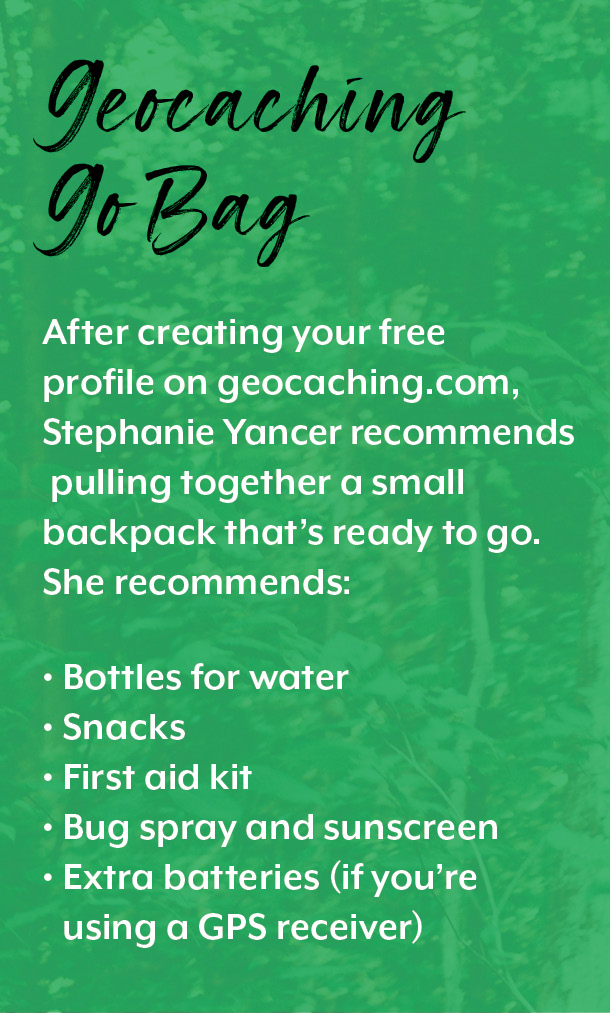

The perfect combination of technology and nature, geocaching started more than 20 years ago in Oregon using decommissioned satellites and longitude and latitude coordinates to locate a specific spot. This outdoor recreational activity uses a GPS receiver or mobile phone to locate a “cache” in a specific location that is uploaded to the official website—geocaching.com. Your average cache is a small, waterproof container that must at the very least contain a logbook and sometimes a pen or pencil. Just as often, tiny toys or tchotchkes can be found with a “take one/leave one” exchange policy. All you have to do to join the fun is create a free profile on the website and prepare to get hooked.

Most of us already hold the key tool in our hands, a mobile device with some navigational ability. Also required is something we all started out with, but have often forgotten along the way–our sense of curiosity.

“Geocaching gives you this fun reason to go exploring,” said Stephanie Yancer, social media coordinator for Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR). “You get out there in the woods or the wild and there is this wave of fun and excitement you can’t help but feel.”

Walking through parks, forests, hilltops, and even urban environments, a cache can be found anywhere. With caches located in 191 different countries, on all seven continents, this global treasure hunt may well speak to our fascination with buried and lost treasure and tug at our inner Indiana Jones. With more than 3 million caches around the world, it’s no wonder there are 7 million active geocachers on geocaching.com.

Locally in Michigan, there are many avid geocachers, including individuals who belong to MiGO (Michigan Geocaching Organization). Steve Bassette, who is the president of the executive committee and an avid geocacher himself, has helped grow interest in the sport, which also promotes environmental stewardship and an appreciation of the outdoors.

“You get out there in the woods or the wild and there is this wave of fun and excitement you can’t help but feel.”

“I ‘accidentally’ came across geocaching when my wife and I were camping and kept seeing a couple hopping on and off their bikes in the woods where we were set up. We finally asked them what they were doing,” said Bassette. “They explained geocaching to us and we’ve been hooked ever since.”

Bassette and MiGO hope to leave the discovery of the sport less up to chance and are determined instead to bring as much attention to geocaching as they can. MiGO has partnered often with the DNR and other organizations to coordinate year-round events, including Camp MiGO every August and specialized events like the Michigan State Parks GeoTour, which celebrated our state parks’ 100-year anniversary in 2019 by placing 100 new caches throughout the state that can now be accessed annually.

“After surveying folks who participated in the GeoTour, we found that people had discovered 80 new parks on average for themselves through the event,” said Yancer. “This is the heart of geocaching—discovering something new.”

Yancer has even found herself discovering things in environments she thought she knew well. While participating in an Adventure Lab, a sort of clue-based cache that involves multiple sites, Yancer took a colleague on a tour of the murals in downtown Bay City, where she works. She saw many wonderfully expressive paintings–some she knew, some she didn’t, and some she was seeing with new eyes.

“It was such a great way to show someone Bay City,” said Yancer. “And to rediscover it for myself.”

Ultimately, geocaching can be as simple or complicated as you want it to be. Each cache is identified by two indicators–difficulty and terrain. You can use your phone or find yourself a GPS receiver. You can look in Antarctica or Ann Arbor for treasure. In the end, it’s your quest.

“The best part of geocaching is the unexpected adventures it takes you on,” said Bassette.