The Jordan River National Fish Hatchery (JRNFH) located in Elmira, Mich., is a Great Lakes Energy Cooperative Member, and is one of the village members who make up the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, a bureau within the Department of the Interior. Jordan River National Fish Hatchery has produced native fish for stocking into the Great Lakes since 1965.

All the work JRNFH does to manage fish stocking into the Great Lakes is coordinated with the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, with key support from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other federal, provincial, state, and tribal natural resource agencies. Their mission to “conserve, protect, and enhance” fish and wildlife is a vital part of righting an environmental ship right here in Michigan that put native trout and other keystone species in danger in the Great Lakes.

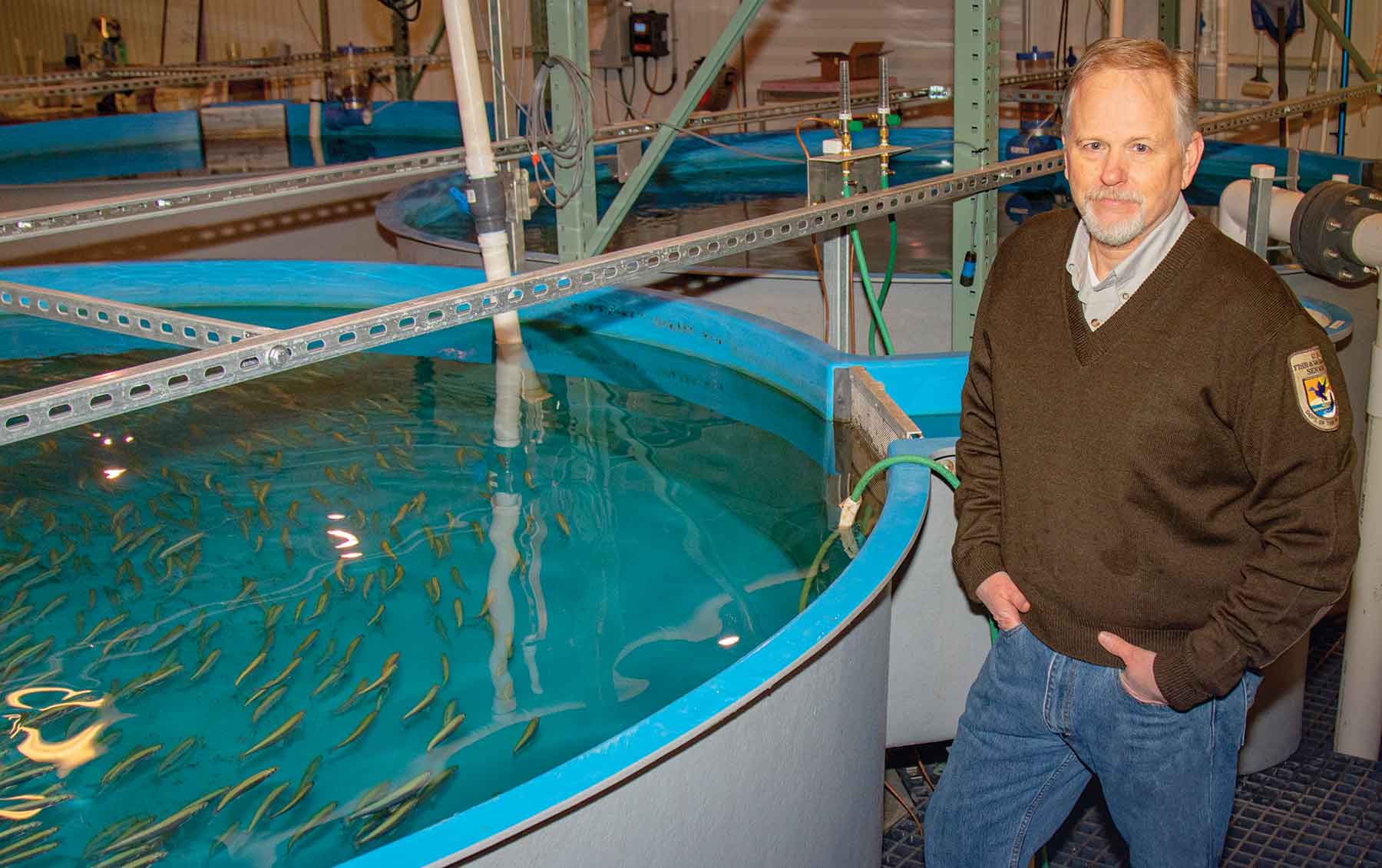

“The threat to these keystone species started in the middle of the 20th century,” explained Roger Gordon, a supervisory fishery biologist and hatchery manager. “There were many contributing factors from a loss of habitat to pollution, and of course, the introduction of parasite species like the sea lamprey.”

Sea lampreys, a native to the Atlantic Ocean, resemble eels but act more like a leech, as they feed on native fish once they attach. The first recorded observation of a sea lamprey in the Great Lakes was in 1835 in Lake Ontario. Niagara Falls served as a natural barrier, confining sea lampreys to Lake Ontario and preventing them from entering the remaining four Great Lakes. However, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, improvements to the Welland Canal, which bypasses Niagara Falls and provides a shipping connection between Lakes Ontario and Erie, allowed sea lampreys access to the rest of the Great Lakes.

Native trout are primary targets for the sea lamprey. The feeding on keystone species like lake trout, which have been in the Great Lakes since the Ice Age, leads to an imbalance in their ecosystem. It’s up to JRNFH and their aligning agencies to observe, control predators like sea lampreys (as well as humans), and restock the lakes to bring back order to the ecosystem. It’s a tall order, which is why Gordon is grateful to be part of a larger team.

“This isn’t a job for just our hatchery,” said Gordon. “We work internationally with Canada, eight other states around the Great Lakes region, as well as federal, state, and tribal agencies, not to mention research universities who help us collect and analyze data.”

JRNFH is responsible for raising more than 3 million cisco, lake, rainbow, and brook trout for restoration and recreational programs in the Great Lakes region. In addition to providing healthy, high-quality fish for fishery goals and targets, the staff assists a wide array of state, federal, tribal, and public partners with natural resource-related projects and enhancements across the Midwest.

It takes a fleet of trucks (think big milk semis) to transport and then load a large U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service offshore stocking vessel. This vessel meets the trucks at various Great Lakes ports like Charlevoix, Alpena, or even Milwaukee with fish. The fish are transported to historic offshore spawning sites and released, and,

as Gordan says, “we let them do their thing.”

Gordon describes himself and his team as “aquatic farmers” who work closely with the animals they raise and release.

“We get our hands wet working with live animals every day,” said Gordon. “There’s nothing particularly pleasant about spawning fish in 15-degree weather with 30 mph gale winds, but there’s satisfaction and an attachment to our mission.”

The hard work is paying off. Since stocking the Great Lakes, JRNFH and its partners have actually eliminated the need for stocking Lake Superior, which is now self-sustaining. Recently, Lake Huron has rebounded as well, with just 30% of what they initially used to stock and over 50% of current fish spawned in the wild. Lake Michigan is proving tougher, but still seeing some improvement.

If the work continues, JRNFH hopes to see a rebalanced ecosystem for native trout—but what happens then?

“Ultimately, our job is to put ourselves out of business. To fix the problem and move onto the next one,” said Gordon. “What we do is a great example of how government can work together in a cooperative manner to get something done. None of us could accomplish any of this without the others.”

Visiting The Hatchery

The hatchery is open to the public from dawn to dusk, 7 days a week, all yearlong. The busiest time of year for visitation is the winter months, when the Jordan Valley snowmobile trail is open. Tours are self-guided unless arrangements for group tours are scheduled in advance. To schedule group tours, please call the hatchery at 231-584-2461. The hatchery abuts the North Country Trail and Jordan Valley Pathway walking trail systems and is a common stop or trailhead for walkers, hikers, hunters, and fishermen.